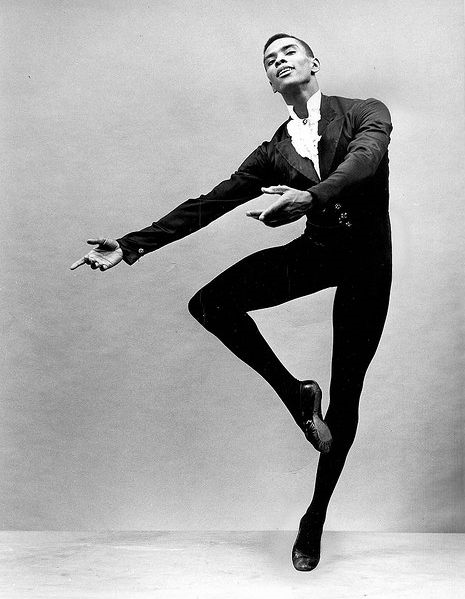

Arthur Mitchell, Photographer Unknown, Date Unknown

By Zita Allen

Excerpted Article

Courtesy of Dance Theatre of Harlem

The first thing one noticed about Mitchell, who passed away at age 84 in 2018, was his handsome, charismatic presence. He had an engaging vitality, elegant bearing, rich dark chocolate skin, chiseled cheekbones, sculptured lips, and the piercing gaze of an observant, intelligent, and doggedly determined soul. “I’m a doer . . . I’m like a bulldozer. Nothing can stop me,” he admitted in 1968 to Ric Estrada, the Dance Magazine writer who had ventured to Harlem to learn about the dance school and ballet company that the first Black dancer with a major American ballet company was in the process of creating.

Mitchell struck the writer as a “practical idealist, a hard-headed, never-take-no-for-an-answer visionary.” In truth, few are blessed with the drive required to transform dreams into reality and by doing so cause a paradigm shift in the way others view the world, but Mitchell is made of sterner stuff than most. “You don’t relax once you’ve reached the first goals,” he told dance critic Tobi Tobias. “You must be continually striving, or you become mediocre.” Thanks to that relentlessness, our perception of what a ballet dancer looks like was altered and the art’s audience appeal was broadened.

Dance Theatre of Harlem, the dance school and Black ballet company Mitchell founded in 1969 with Karel Shook, was a product both of his visionary genius and belief in the transformative power of art. However, it was equally a product of the cultural, social, and political forces of the era that gave birth to it. While the history of DTH has much in common with other newly created cultural institutions in the 1960s, its founders, dancers, repertory, and audiences are, in many ways, distinctive.

Arthur Mitchell, Photographer Martha Swope

First in the impressive “bio” of the man who had conceived the idea, came Lincoln Kirstein’s historic invi- tation to a young Harlem-born, modern-dance-trained graduate of the High School of Performing Arts to study, on scholarship, at the School of American Ballet. Then, in 1955, the invitation to join New York City Ballet, followed in 1958 by a promotion to soloist, and in 1962 to principal, making Mitchell this country’s first African American to attain that rank with a major ballet company.

By 1967, the thirty-three-year-old internationally acclaimed dancer was commuting between NYCB in New York and Rio de Janeiro, where, under an agreement with the U.S. State Department and Brazil’s Ministry of Education and Culture, he was hired to help organize the Companhia Nacional de Ballet, the country’s first federally-funded ballet company.

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, triggered the epiphany that prompted Mitchell to change course and begin the process that would spark a cultural sea change with the creation of the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Mitchell recalled his reaction to the King assassination: “I was very upset and got very emotional, and I said, ‘Why should I be going to Brazil when there are so many problems here at home?’ Dorothy Maynor had the Harlem School of the Arts, and she had been asking me to teach for her. So, I went up there, it was on 141 Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, a bare-bones garage with a hot tin roof. I took my own personal money—$25,000— and put in a dance floor and barres. We couldn’t afford mirrors. I charged fifty cents a week, and I just told kids to come in because I felt it was very important to take young people off the streets and get them involved in the arts, and particularly dance.”

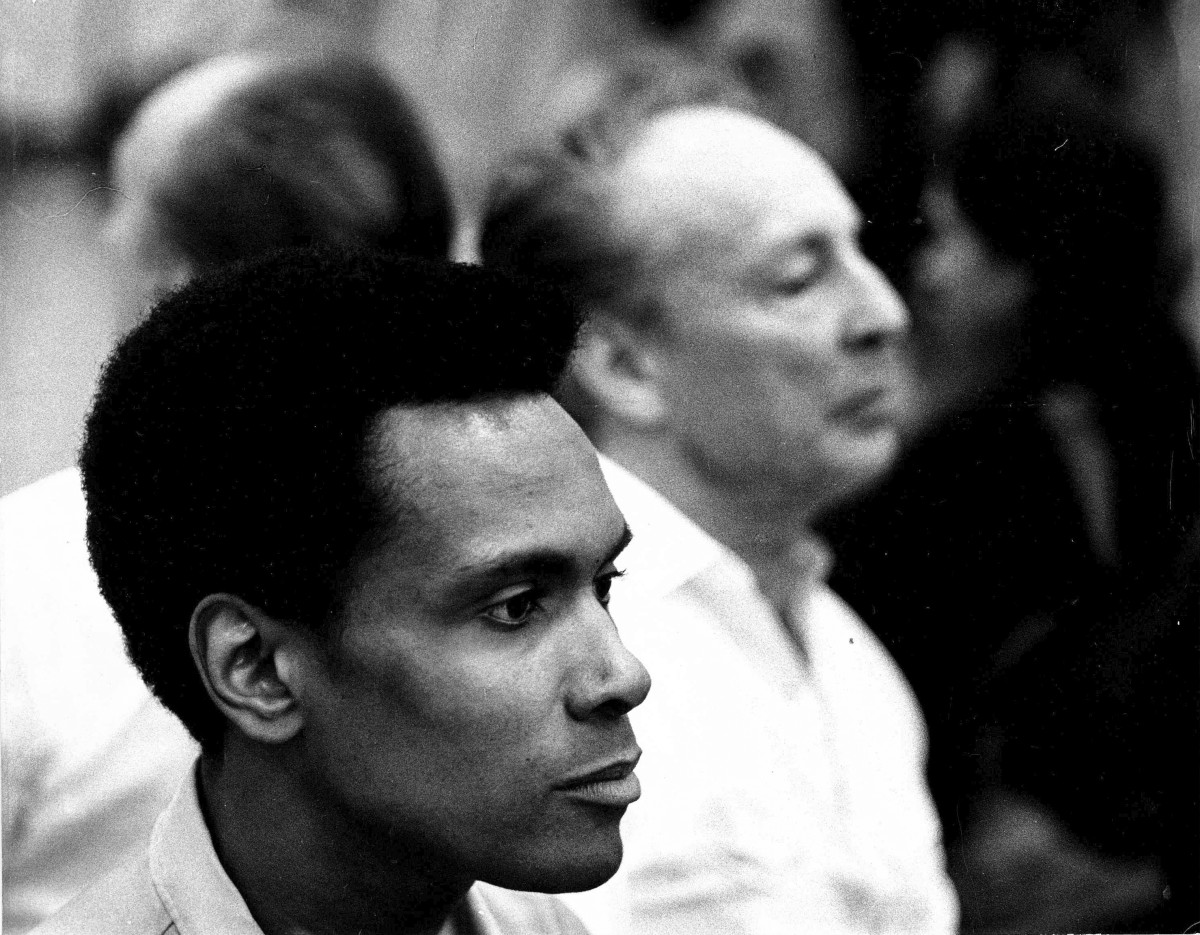

Arthur Mitchell, George Balanchine, Photographer Martha Swope, Concert for Jazz Band and Orchestra

By May 6, 1971, three years after the 1968 Dance Magazine interview, the New York City Ballet’s Eighth Annual Spring Gala at the New York State Theater in Lincoln Center said more about Mitchell’s ground- breaking enterprise than a review or feature article ever could. The highlight of the performance was “Concerto for Jazz Band and Orchestra,” choreographed by NYCB’s founder and artistic director George Balanchine and Mitchell.

Balanchine later wrote, “It was a wonderful thing for me to collaborate on the choreography with Arthur Mitchell, who had become, in the New York City Ballet, the first black dancer in any major ballet company . . . The Dance Theatre of Harlem, and its associated school . . . [are] one of the great breakthroughs in the arts in America.”

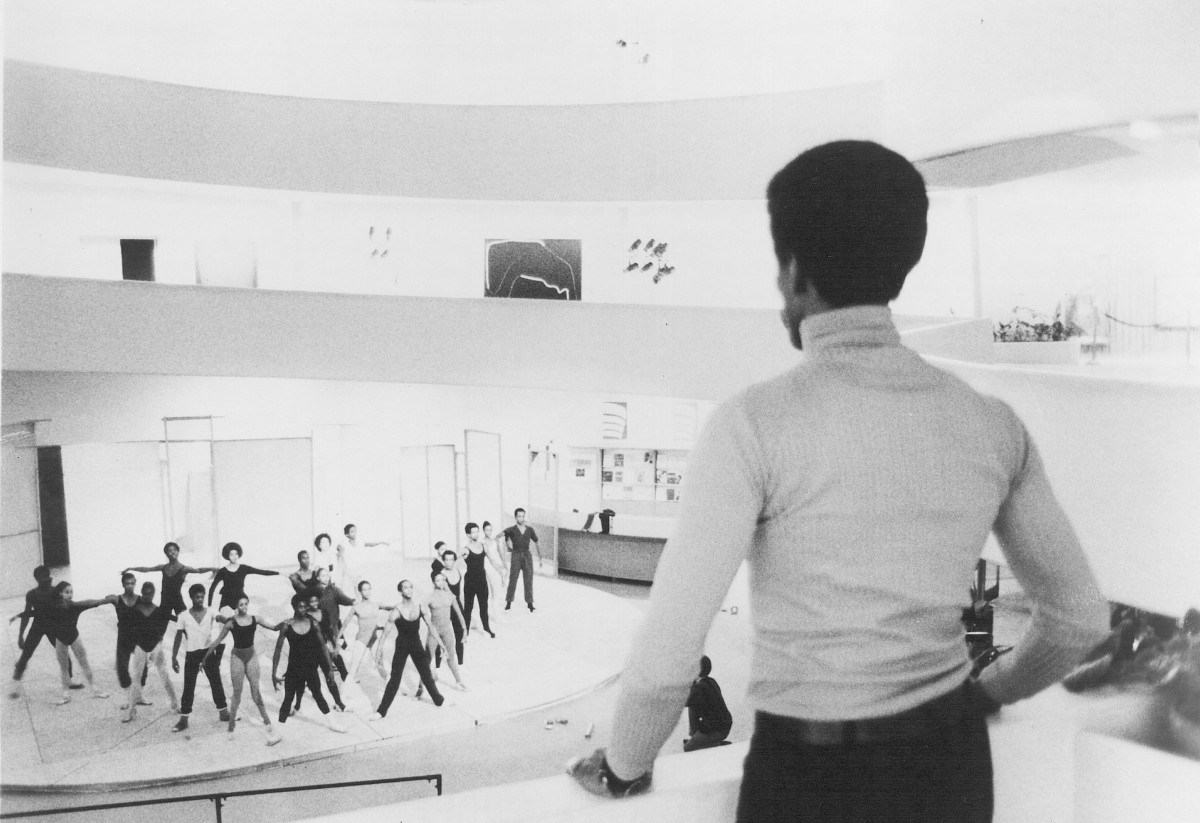

Guggenheim V Mr. Mitchell Arthur Mitchell Foreground, photographer Martha Swope

DTH was not the first ballet company created as a platform for ballet-trained Black dancers in an art from which they had been systematically excluded. As Mitchell told Dance Magazine, “There were always black classical dancers in America—they just never got on stage!” Later, in a 1974 interview with London Times critic John Percival, he said, “We don’t want people to think of us as a black ballet company. Of course, we are black, and because we are the first, that is the point of interest that gets people into the theatre. But after watching, even just for three minutes, I hope you forget that. What matters is not the color of the skin, but whether a dancer is a good dancer or not.”

As Karel Shook wrote, it goes without saying that Arthur Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem added, “a new dimension to the world of theatrical dance” as much as it has served as a “testament to the expansive richness of the art and the tenacity of artists who happen to be black.” In addition, what so many writers referred to in the beginning as the miracle of Dance Theatre of Harlem has been both about the transcendent power of tenacity and the transformative power of art and culture in the struggle for social, economic, and artistic self-determination and justice.

Read the complete essay here.

This excerpted article was written by Zita Allen, provided courtesy of Dance Theatre of Harlem, and is featured in the Dance Theatre of Harlem 2024 New York Season Magazine.

Zita Allen, dance writer for the New York Amsterdam News, was the first African American critic for Dance Magazine, founding contributor to ’70s Black dance publication The Feet, and has written for Ballet Review, Village Voice, SoHo Weekly News, New York Times, and Essence. She authored Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, 25 Years, the Kennedy Center’s Masters of African American Choreography, the American Dance Festival/PBS Free to Dance documentary’s companion website, Black Women Leaders of the Civil Rights Movement (Scholastic), contributed to the Encyclopedia of African- American Culture and History (Macmillan), Smithsonian’s Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing: How the Apollo Theatre Shaped American Entertainment (Random House), and “Arthur Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem: The Early Years”

for Columbia University Library’s Arthur Mitchell: Harlem Ballet’s Trailblazer. She holds an M.A. from NYU in Dance History, taught “The Black Tradition in American Dance” for the Ailey/ Fordham BFA program, guest lectured at Juilliard, and Temple University where she is pursuing a Ph.D.in Dance Studies under a University Fellowship.