You don’t have to know an artist’s name to know their work. And while you may not necessarily know the name Edward Gorey, you certainly have seen his macabre legacy all around you.

Gorey was an American writer, Tony Award-winning costume designer, and artist noted for his own illustrated books as well as cover art and illustration for books by other authors. His signature style of illustration is a drab cross hatching of frail figures in Edwardian garb with large vacant eyes pondering, or entirely not expecting, their impending doom. Ornate urns and curving furniture fit for an English manor lurk in the corners of each panel, and the empty space between is filled with a sense of things about to go most terribly wrong. A sinister whimsy suffuses the pages and a dry comedic touch chuckles at the bleakness of being.

Maybe you know Edward Gorey’s work from the iconic introduction to PBS’ Masterpiece Mystery, featuring pallid figures who are dancing in the moonlight, questing for clues, or swooning dramatically over ledges. Or maybe you have read The Gashlycrumb Tinies, a slim volume trailing through an alphabet of children and the varied ways their lives end

(“E is for Ernest who choked on a peach”).

And if you’ve ever seen a Tim Burton film, gotten lost in the wry humor of A Series of Unfortunate Events, shuddered at Neil Gaiman’s Coraline, reveled in the Victorian strain of gothic subculture, or even rocked out with the music video for Nine Inch Nails’ “The Perfect Drug” playing in the background – then you’ve submerged yourself in the tradition of Edward Gorey and the imaginings of artists who credit him as a key influence.

Now you might imagine that, when asked who Edward Gorey himself considered to be an inspiring hero, he would have referenced someone such as an antiquated gothic novelist with plots as twisted as their winding corridors or a medieval muralist with faded panels depicting anguished peasants dancing amongst the bodies of their plague-stricken loved ones. However when asked who his hero was, without pausing for breath, Edward Gorey said George Balanchine.

What could the grandfather of goth and the father of American ballet possibly have to do with one another? Far more than you might think. Edward Gorey was undeniably obsessed with ballet and was transformed as an artist because of it.

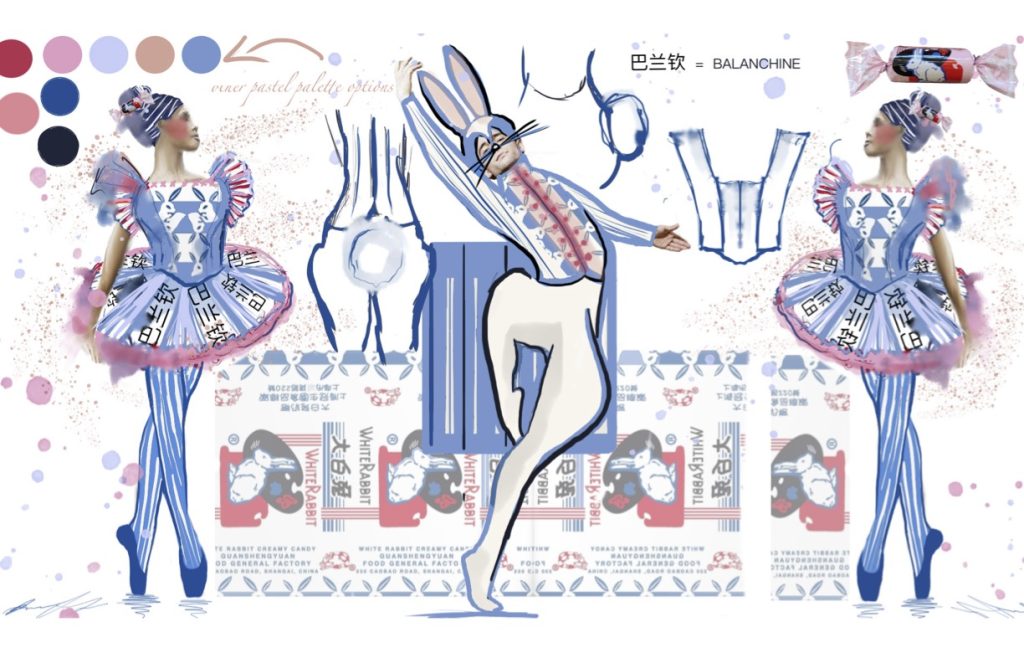

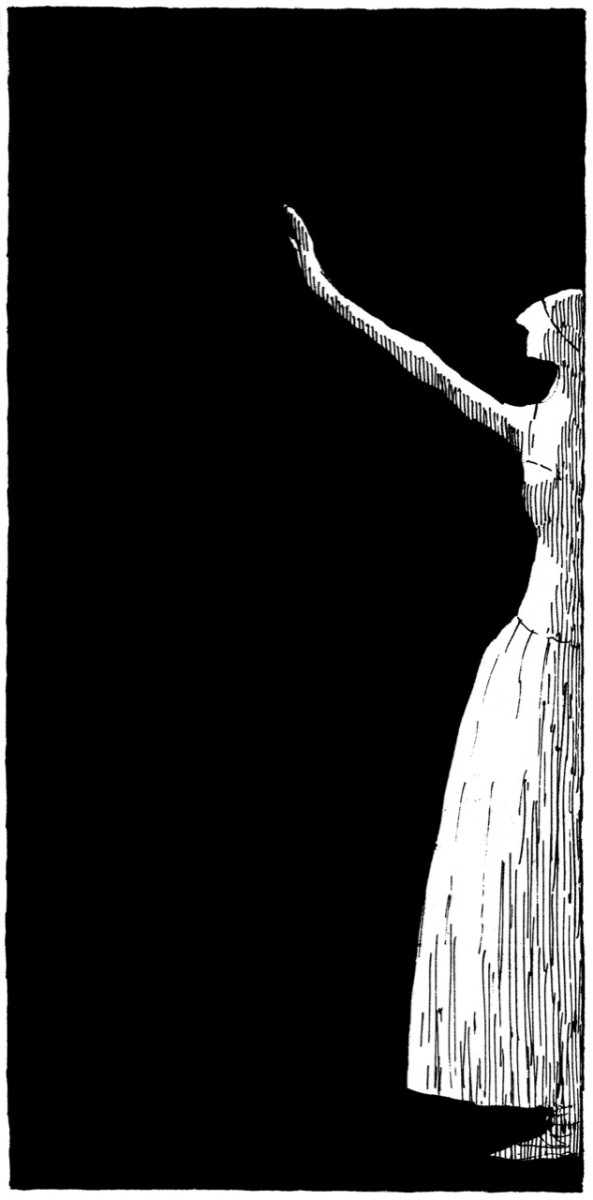

Gorey’s illustration to Serenade for a Ballet Review cover (No 1, 1975-76)

Images courtesy of The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

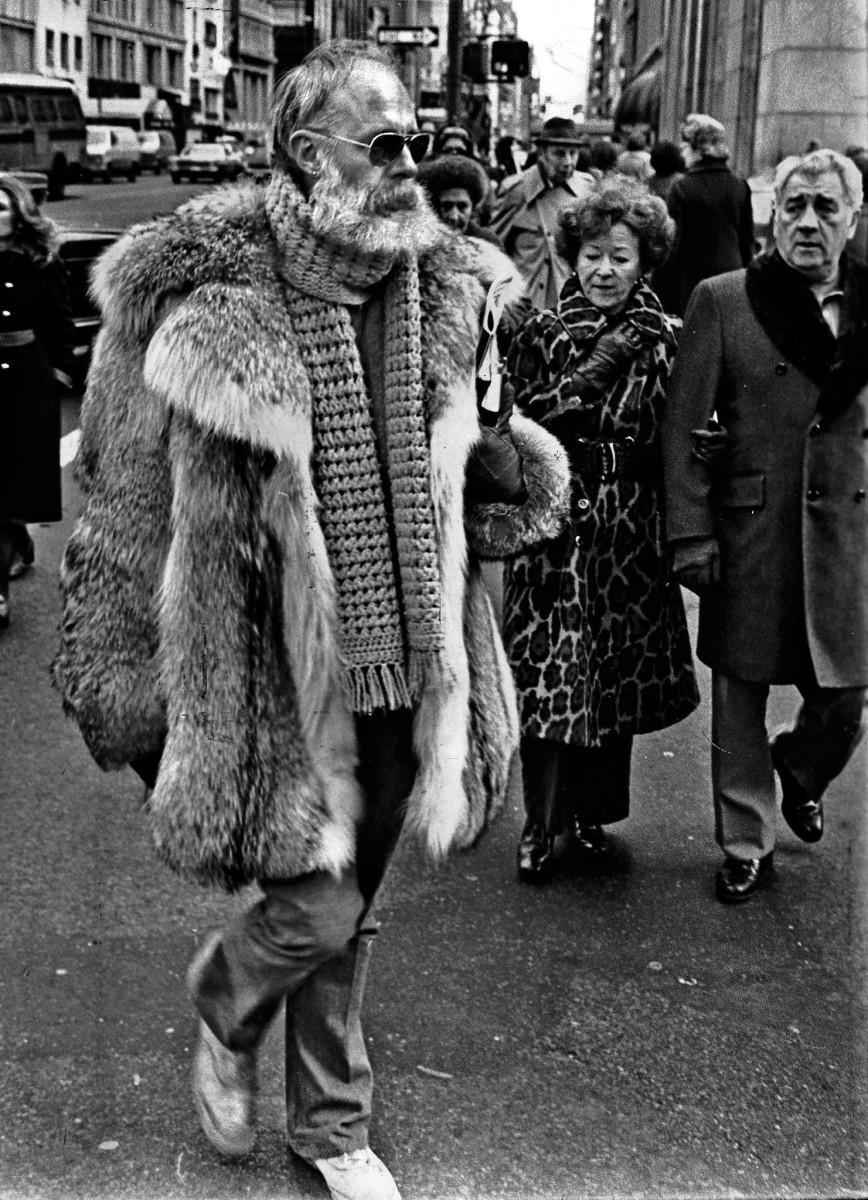

Gorey was a man of precise routines and patterns, and in the 1950’s he began to weave nearly every single performance of the New York City Ballet into his life. He would arrive promptly when the theater doors opened with a book held in his ring-encrusted hands. Clad in a vibrant yellow fur coat that skimmed the floor along with converse shoes and a beard fit for a sea captain, he became such a familiar figure in the City Center that a regular ballet patron could be forgiven for starting to wonder if Gorey lived in the theater itself.

Many would claim that he saw every single performance the company held, and while that is not quite true, it is nearly so. Friends claimed that he saw at least 160 ballets a year, and The New York City Ballet states that he watched 78 performances of The Nutcracker within the span of just two seasons. With these types of numbers, describing Gorey as a devoted fan seems like an understatement. A religious devotee worshiping at a temple feels more apt. The Edward Gorey House currently has many of the ticket stubs he collected on display. From Agon to The Nutcracker, hundreds upon hundreds of bright squares of cardstock commemorate nearly thirty years of watching Balanchine bringing American ballet to life and into the modern world.

Not that Gorey was always enthralled with each piece. If he wasn’t impressed with an evening’s lineup he would spend time in the lobby with his book or in the middle of a cluster of other ballet aficionados trading gossipy commentary. If it was a favorite piece, he would come back for every casting variant, looking for and cherishing the details that made each performance unique in that one ephemeral moment from any other in the run.

And while he did occasionally watch dance offerings from other contemporary choreographers, it was the work of George Balanchine himself that held him in thrall. In a 1974 interview he said, “I feel absolutely and unequivocally that Balanchine is the great genius in the arts today… My nightmare is picking up the newspaper some day and finding out George has dropped dead.”

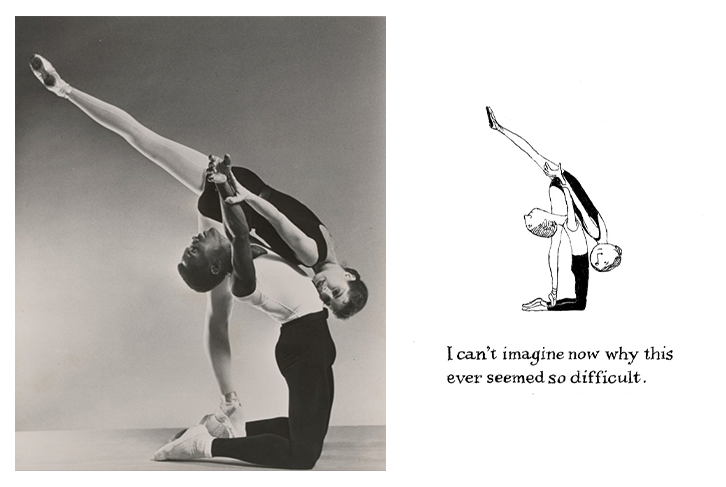

This balletic fixation transformed Gorey and his illustrative style. He crafted overt homages such as

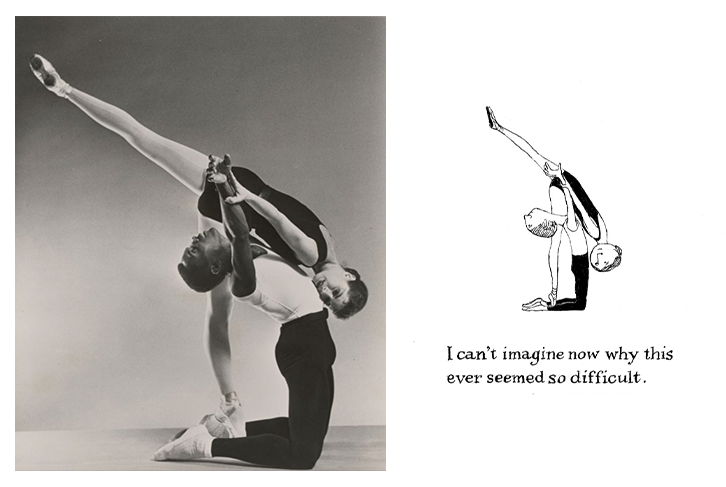

The Gilded Bat which features a girl given to staring at dead birds becoming a chic and mysterious prima ballerina, all before of course meeting an untimely death. But the impact of ballet is seen more subtly, more deeply, in the way in which Gorey drew bodies. He would capture lines of movement, frame stage-worthy compositions, and extend limbs that seemed as if they were steps frozen in time from a dance, because they often were.

This balletic fixation transformed Gorey and his illustrative style. He crafted overt homages such as The Gilded Bat which features a girl given to staring at dead birds becoming a chic and mysterious prima ballerina, all before of course meeting an untimely death. But the impact of ballet is seen more subtly, more deeply, in the way in which Gorey drew bodies. He would capture lines of movement, frame stage-worthy compositions, and extend limbs that seemed as if they were steps frozen in time from a dance, because they often were.

This choreographic nature of Gorey’s work has not gone unnoticed. Choreographer Peter Anastos, collaborated with Gorey to adapt

The Gilded Bat into a ballet for Ballet West, and they even partnered together in a separate project to create their own absurdist variant of Giselle.

More recently The Trey McIntyre Project performed Vinegar Works: Four Dances of Moral Instruction, a farewell piece from Trey which was not merely inspired by Gorey, but was centered around The Gashlycrumb Tinies, telling in dark disturbing steps with a voice reading off the ways these little ones met their deaths. And so in a Goreyesque twist of fate, art that was influenced by ballet, became ballets themselves.

To celebrate this balletic connection, The Edward Gorey House is currently running an exhibit titled “Doing the Steps: Edward Gorey and the Dance of Art.” Curator Gregory Hischak, while not a ballet expert himself, has now immersed himself in this world because to love Gorey is to, at least at some deeper level, love ballet.

When discussing this relationship Hischak said, “Movement and pacing, the storyless stories and fragmented narratives — all aspects of Balanchine’s world — are reflected in Edward’s own works. In fact, ‘Doing the Steps’ invites the notion that virtually all of Edward’s books function as dance pieces.”

Ballet is a lovely art form when it is in the spotlight – it continues to hold its own in the contemporary art landscape with the stunning live performances we cannot get enough of. But ballet lives boldly beyond the confines of the marley floor. Once you step outside of the bright stage lights and adjust your eyes to a shadowier scape, you will find grand jetes in pop culture, pirouettes in underground poetry, and yes, a ballet-obsessed illustrator at the beginning of modern gothic aesthetics.

Because ballet bleeds into everything, including the bloody pages of Gorey.

Image One: Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library. “Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in “Agon”” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1957. Image Two: Gorey’s Illustration to The Lavender Leotards, (1973) (“I can’t imagine why this ever . . .”) Image courtesy of The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

Much thanks to Gregory Hischak of the Edward Gorey House.

Read more via the following resources:

Edward Gorey Biography

The Paris Review

Edward Gorey Charitable Trust