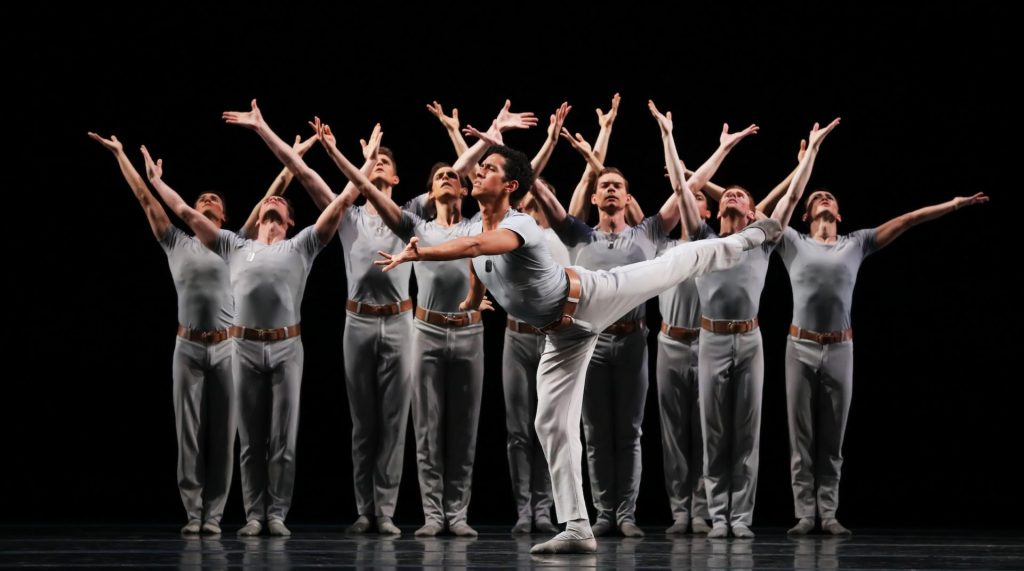

Jessica Lind and Brian Simcoe in Danielle Rowe’s Dreamland. Photo by Jingzi Zhao.

Danielle Rowe: Creating Constraints and Transporting Audiences

Asked why he wanted OBT to perform Danielle Rowe’s Dreamland, artistic director Peter Franc refers to the time he and Rowe shared as dancers with Houston Ballet. “Dani always brought meaningful nuance and detail to all her movement, no matter the style. As I followed her choreographic journey over the years, it was clear that her creative mind contained no boundaries and has a fresh and unique style the dance scene yearns for.”

But Danielle Rowe never intended to be a choreographer. So how did this classically trained ballet dancer from Australia, who was happy to be a self-described “vessel for the choreographer,” during her 15 years on stage, grow into a creator with such an innovative, stylistically diverse voice? Let’s find out.

How did you get started in dance?

Like so many dancers, I was a hyperactive kid. My mum put me in any kind of activity that would release some energy, and ballet was one of them. I really took to it; was completely absorbed and captivated by it. So my mum just kept taking me— I think she was at her wits’ end. This was in Adelaide, where I grew up.

When did you become more serious about ballet?

I’d been doing every sort of dance— jazz, tap, musical theater— but around 10 or 11, my ballet teacher said I had to choose because tap was making my ankles too loose for ballet. When I was 14, I moved away from home to train full time, first at a school in Newcastle, then at the Australian Ballet School. And after I finished my training, I joined the Australian Ballet, where I danced for ten years.

How—and why— did you move to the US?

After Christopher Wheeldon staged his ballet After the Rain on us at Australian Ballet, he ended up inviting me to join his company, Morphoses. So I took a leave from AB and spent two seasons touring all over the world with them. Being exposed to so many dancers and learning how other companies operate made me think I was ready to try something else beyond the Australian Ballet.

I’d worked with Houston Ballet’s artistic director, Stanton Welch, quite a bit in Australia, and he generously offered me a job. It was a wonderful opportunity to find my feet in another company, but by then I was starting to feel this urgent desire to move differently. I’d always been fascinated by Nederlands Dans Theater, so I reached out to them to see if they might be interested in working with me. And they were!

Most dancer-turned-choreographers say they always were making dances in some way, long before officially choreographing a piece. How did you get into choreography?

I never thought about choreographing when I was dancing. I just loved being part of the creative process as a vessel for the choreographer. But like most dancers, I think, I’d hear music and have ideas and imagination, but I never pursued anything. To be completely honest, I just didn’t have the confidence that my ideas were worth being put out there.

After three years with NDT, I felt content with the career that I’d had. I’d worked with these incredible dance makers and was really fulfilled. I had been traveling back and forth on weekends to see my husband, Luke Ingram, who is a principal dancer with San Francisco Ballet. We were both just exhausted. I had no idea what I was going to do next, but I’d always wanted to start a family. So I moved back to the US, and a few months later I was pregnant. I just wanted to take a breath and focus on being a mum.

After three years with NDT, I felt content with the career that I’d had. I’d worked with these incredible dance makers and was really fulfilled. I had been traveling back and forth on weekends to see my husband, Luke Ingram, who is a principal dancer with San Francisco Ballet. We were both just exhausted. I had no idea what I was going to do next, but I’d always wanted to start a family. So I moved back to the US, and a few months later I was pregnant. I just wanted to take a breath and focus on being a mum.

What got you back into the studio?

Well, after my eldest daughter was born, I did get involved with advising and helping out a project-based dance company called SF Danceworks. At one point, they needed a new piece of work, and a friend reached out to me and said, “Dani, I think you should choreograph for this.” I resisted, but I think he knew me better than I knew myself. I started working on a solo for him and it was like, ‘Okay, this feels good…” The solo became a duet which ended up being performed at a gala for Bay Area dance companies. And then I started getting offers and commissions and it just kind of snowballed from there.

Now you have quite a stylistically eclectic body of work. Where do you get your ideas or inspiration?

I think of each piece as research: diving in, finding new ways of moving, experimenting with my thoughts, vision, a story or just an expression of my interpretation of the music. I love constraints; finding things that challenge me. If I’m not given any by whoever’s commissioning the work, I give them to myself.

I look at the company I’m creating for, the dancers, their repertoire, and what they want to get out of the piece. Do they want to be challenged by ballet technique or get into something more contemporary? I think of the company and the dancers— and the audience, of course— as my clients. I’m trying to provide the most substantial and fulfilling experience.

What was your specific inspiration for Dreamland?

I’d been commissioned by Ballet Idaho. It was getting closer and closer to the start of rehearsals, and I had no ideas— I didn’t even know where to start. I began having these anxiety dreams where I was trying to claw my way out of a dirt hole and just couldn’t get out. Essentially, I was digging my own grave. The visuals were so stark and had a Gothic feel: I had these long nails, almost monster-like. I woke up one day and thought, that’s it. I’d start with this movement quality of monsters, creatures, and that feeling of anxiety, that something’s around the corner you can’t get away from.

I researched Gothic artists and found a painting by Henry Fuseli called The Nightmare. It’s a woman in a white nightgown, asleep, with a demonic, gargoyle figure looming over her. The ballet also incorporates the thread of a calming, assured force that’s inspired by a childhood friend of mine, who passed away when I was very young and still visits me in my dreams.

What constraints did you put on yourself for Dreamland?

My two challenges were that I wanted to include a balletic element juxtaposed by a contemporary, grounded feel, and wanted to make a big group piece because I hadn’t done that before.

What do you want Portland audiences to take away from Dreamland?

I just want them to be transported into a world of their choosing, and to get lost in it. Whether because it reminds them of something they’ve experienced, or they’re interested in the movement or get carried away by the music. I think my signature is that my pieces are all-encompassing theatrical experiences, not simply dance on a stage. So I hope they are zoomed in and not thinking about anything else.

![]()

~Gavin Larsen

Former OBT principal dancer Gavin Larsen is the author of Being a Ballerina: The Power and Perfection of a Dancing Life (University Press of Florida)

This article was first published in the Dreamland playbill. It is published here courtesy of Oregon Ballet Theater. Click here to learn more or read the entire playbill.