Imagery trained and prompted by Hamill Industries featuring Samantha Bristow

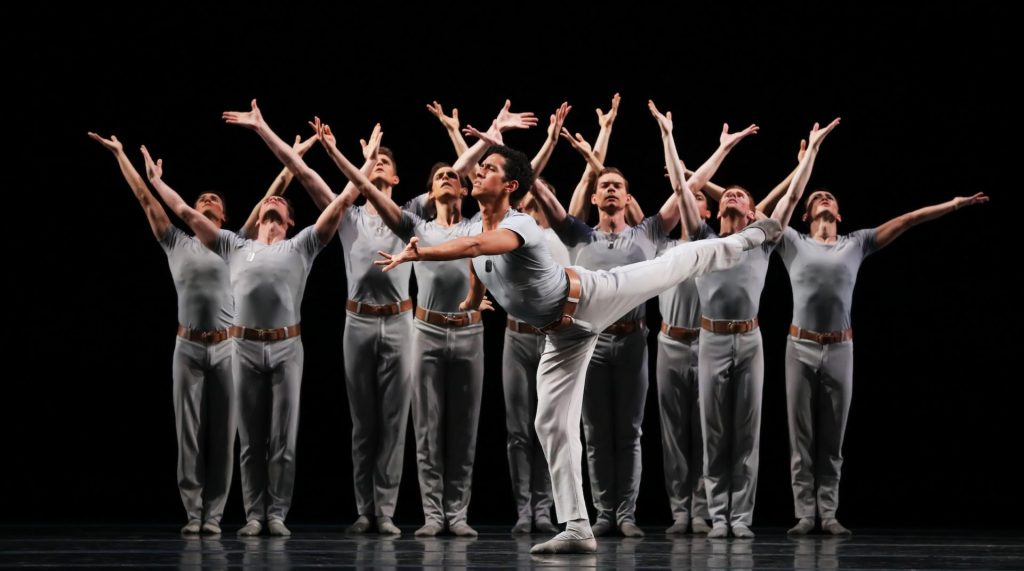

Courtesy of San Francisco Ballet, source photo by Lindsey Rallo

“It’s important that the work we do at SF Ballet is relevant not only to the company, but to the people who live here in the Bay Area, and many of us are considering the role of artificial intelligence in society and in our individual lives. Mere Mortals began with a conversation about the philosophical questions that have emerged and will continue to emerge from this new technology. We wanted to find a story from history that engendered these same philosophical questions. We landed on the Prometheus and Pandora myths: the stealing of fire, which was both positive and an incredible danger, and the opening of the box. These are the first times that humanity openly disregards profound consequences in the pursuit of knowledge—and yet humankind has always moved forward despite the risks.”

—Tamara Rojo, San Francisco Ballet Artistic Director

Daphne Koller is a Machine Learning pioneer and the founder and CEO of insitro, a biotech company that leads AI-driven drug discovery. She is also the co-founder of the online learning platform Coursera, and was a professor in the department of computer science at Stanford University and a MacArthur Foundation fellowship recipient.

How has the development of AI changed over the last five years? And how do you think it will change in the next five, ten, or fifteen years?

We’re on what is clearly an exponential curve in terms of the capabilities of this technology, but the challenge of an exponential curve is that the human mind doesn’t really understand it. It’s really hard for us to understand something that gets twice as good every year. But you can look back and observe the capabilities of the technology in, say, recognizing what’s in an image. If you go back ten years, it was barely at the level of, “oh, I think I see a dog.” The technology we have today can not only write an entire story about what’s in an image, but can even generate an image based on a verbal description. So we can say: “Could you make the dog jump higher, be furrier, be friendlier?” with all

sorts of qualitative descriptors, and the machine will generate something that looks real. Because this is an exponential curve, it’s very difficult to foresee even two to three years ahead, let alone ten years ahead.

What is the potential you see in using AI as a tool for accessibility to something like arts, education, or healthcare?

Those are quite different use cases.

If I had to generalize, I would say that those are going to be transformative to accessibility but in different ways. In the arts, if you think about someone who is, for example, visually impaired and having the computer be able to describe what is being perceived in ways that anyone can understand, or conversely, if you’re someone who’s hard of hearing, you can make a piece of music and create visual imagery that’s evocative of what’s being played, which I think is incredibly exciting. In education, I think that this is going to be a truly transformative capability. There’s a study by Benjamin Bloom from 40 years ago called “the two sigma problem,” where he showed that a student who has access to a private tutor performs two standard deviations better than a student who’s in a standard classroom. The problem is that we’ve never had the ability economically to provide a private tutor to every student, but now we can. So there’s the opportunity to take kids who are basically performing at median or even far below the median and “up level” them in a way that would not have been imaginable without this technology.

This article was provided courtesy of San Francisco Ballet