Images courtesy of Pacific Northwest Ballet.

“In Westphalia, the former Saxony, all is not dead which lies buried. When we wander there through the old oak groves we can hear the voices of the olden time, and the re-echoes of those deeply mysterious magic spells in which there gushes a [great] fullness of life …A mysterious awe thrilled my soul—when…wandering through these woods”

—Heinrich Heine, On Germany [1833],

trans. Charles Godfrey Leland

Libretto: Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Théophile Gautier

Music: Adolphe Adam (1841), with additional music by Friedrich Burgmüller,

Riccardo Drigo, Ludwig Minkus

Choreography: Jean Coralli, Jules Perrot, and Marius Petipa,

with additional choreography by Peter Boal

Staging: Peter Boal

Historical Advisers: Doug Fullington and Marian Smith

Scenic and Costume Design: Jérôme Kaplan

Lighting Design: Randall G. Chiarelli

Original Production Premiere: June 28, 1841; Ballet du Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique (Paris), choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot

Petipa Production Premiere: February 5, 1884; Imperial Ballet (St. Petersburg), choreography by

Marius Petipa (after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot); revived 1889 and 1903

Pacific Northwest Ballet Premiere (Peter Boal Production): June 3, 2011; new production May 30, 2014

The idea for Giselle (1841) was inspired by two ghost stories, both read with relish by Théophile Gautier, the colorful balletomane, poet, critic, man-about-town, and staunch defender of Romanticism. One was a poem by Victor Hugo, “Phantoms,” about a beautiful young girl whose love for dancing leads to her demise. Gautier’s other literary inspiration was a passage in Heinrich Heine’s On Germany, about Wilis, spectral brides who rise from their graves at midnight to dance beguilingly in the moonlight:

In parts of Austria there exists a tradition … of Slavic origin: the tradition of the night-dancer, who is known, in Slavic countries, under the name Wili. Wilis are young brides-to-be who die before their wedding day. The poor young creatures cannot rest peacefully in their graves. In their stilled hearts and lifeless feet, there remains a love for dancing which they were unable to satisfy during their lifetimes. At midnight they rise out of their graves, gather together in troops on the roadside and woe be unto the young man who comes across them! He is forced to dance with them; they unleash their wild passion, and he dances with them until he falls dead. Dressed in their wedding gowns, with wreaths of flowers on their heads and glittering rings on their fingers, the Wilis dance in the moonlight like elves. … They laugh with a joy so hideous, they call you so seductively, they have an air of such sweet promise, that these dead bacchantes are irresistible.

Gautier responded to Heine’s words by saying aloud, “What a pretty ballet this would make!” Then (as he recalls):

In a burst of enthusiasm, I … took up a large sheet of fine white paper and wrote at the top, in superb rounded characters, “Les Wilis, a ballet.” But then I began to laugh, and I threw the sheet aside without giving it a further thought, saying to myself, with the benefit of my journalistic experience, that it was quite impossible to transpose onto the stage that misty, nocturnal poetry, that phantasmagoria that is so voluptuously sinister, all those makings of legend and ballad that have so little relevance to our present way of life. That same evening I was wandering backstage at the Opéra with my mind still full of [Heine’s] ideas, when I met that amusing man [Vernoy de Saint-Georges, who had written the stories for successful ballets]… I related the tradition of the Wilis, and three days later the ballet of Giselle was written and accepted. In another week Adolphe Adam had sketched out the music, the scenery was nearly ready, and the rehearsals were in full swing.

Gautier overstates the brevity of the timetable here—the ballet actually took about two months to create. But the Opéra’s director Léon Pillet did indeed push the project along with unusual urgency, hoping to capitalize quickly on the popularity of the ballerina Carlotta Grisi, who had recently caused a sensation dancing in the Donizetti opera La Favorite.

The scenario they created is set in Germany sometime in the historical past, its first act taking place in a sunny village, and centering round Giselle and the handsome young man who woos her ardently. In the second act, however, all is plunged into darkness: Giselle, who has died of a broken heart at the end of Act I, now must join the band of vampire-like female ghosts, the Wilis, though she ultimately refuses to follow the cruel commands of the Wili Queen, Myrtha.

In fashioning the characters and action, Gautier and Saint-Georges incorporated subjects we now recognize as central to much Romantic art and literature: the lives of country folk, the historical past, the supernatural, the power of transcendent love, the seeking of the unattainable. They also placed the action in an idealized, locale foreign to France—something typical of French Romantic ballets (though the then-obvious German setting, which was signaled to Parisian audiences by the frequent use of waltz music and the names of the leading couple, is no longer instantly recognizable as such). And they called for ethereal female dancers in long white tutus on a darkened stage, a visual motif that had been popularized by the ballet of the ghostly nuns in the opera Robert le diable (1831) and the white-clad forest-sprites of the ballet La Sylphide (1832), two works that had flourished at the Opéra in the decade leading up to Giselle’s premiere. So it is not hard to imagine why Giselle was so successful in the era it was first devised.

But why does it remain so popular today? Performed every season by major companies around the globe and the subject of several popular books, Giselle is also widely available on commercial video, and some of its scenes have even been featured in Hollywood films. How do we account for the continuing success of this ballet? Why is Giselle still so compelling?

One reason is surely the effective way it shows the intrusion of mysterious and alluring-yet-threatening supernatural beings into the lives of everyday mortals—a subject that seems not to have lost its appeal. The encroachment begins in a merely abstract way in Act I: Giselle’s mother Berthe warns the young village women that excessive dancing could lead to their early demise and thus their forced enlistment into the band of Wilis. But Berthe’s description of the Wilis leaves Giselle unfazed and nothing more is heard of these ghosts for the rest of the act.

Berthe’s words of warning become creepily true, however, in Act II which is set on a moonlit night in the Wilis’ territory, a forest glade near a pond. Any mortal male to enter this danger zone does so at his peril. Sure enough, two batches of men do wander in, early in the second act, though they manage to escape quickly. It is another matter entirely for Giselle’s major male characters, however, whose encounters with the Wilis change their lives profoundly and irrevocably.

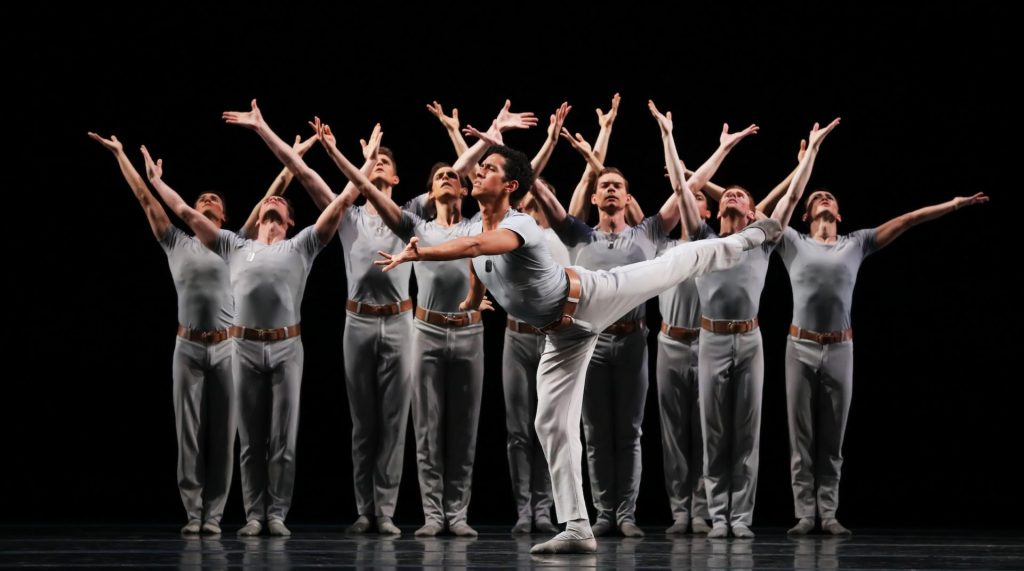

Every element of the ballet—the choreography, lighting, sets and costumes, and music—helps communicate the unfathomable contrast between the real world and the unreal one that lies at its heart. The dancing in the first act is light, airy, carefree, and, in the case of the leading couple, reflective of their lively flirtation. In the second act, however, the range of moods expands greatly, and with it the range of the choreography, which includes, for the Wilis, playful and aggressively vengeful dances as well as drill-team-like formations that demonstrate both their solidarity (sisterhood is powerful!) and obedience to their Queen. And Giselle and Albert dance two pas de deux in which the choreography shows the deep and desperate love they have for each other.

The composer Adolphe Adam did his part in conveying the ballet’s central dualism by creating two very different sound worlds, one for each act. The “color” of the first act is bright, mostly in major keys, featuring waltzes and nineteenth-century hoedown music when the villagers dance, and a majestic march for the noble hunting party. In the second act, however, the music creates an appropriately dangerous and uncertain atmosphere, though tinged with a hypnotic sweetness at Myrtha’s first appearance. Adam accomplishes all this—including bringing out the Wilis’ twofold nature—by deploying many more flat-side keys and unstable harmonies than he did in the first act, as well as minor mode, special effects (like muted strings, tremolo, and harmonics), and plenty of lower brass.

Of course the title character Giselle, the very embodiment of the contrast between the real and unreal worlds, surely accounts for much of Giselle’s enduring popularity. She is a sparkly, high-spirited young person whose ghostly return in Act II as a Wili makes for a stunning character transformation.

Though the world has changed radically since 1841, Giselle retains its power, and there can be no doubt that Gautier’s initial idea to make a ballet out of Heine’s Wili story was a good one. Originally wrought through the great teamwork of specialists in music, literature, drama, choreography, and art design, this ballet has been carried forward for well over a century and a half by successive generations of creative artists. Each new performance brings to life anew the spirited young title character and her milieu and allows audiences today to breathe in the same Romantic air that so inspired Gautier those many years ago.

Notes by Marian Smith.

Portrait of Carlotta Grisi in the title role of Giselle, 1842. Engraving by J. H. Robinson, after a painting by A. E. Chalon

This article was first published in the Giselle playbill. It is published here courtesy of Pacific Northwest Ballet. Click here to learn more or read the entire playbill.