I first met Septime Webre, Hong Kong Ballet’s Artistic Director, in 2018 while working on the role of the White Rabbit in his ALICE (in wonderland). I had spent weeks working on my interpretation of the role prior to his arrival; I preciously went over how I wanted to approach each step, my character arc, and each rabbit-like thump of my foot. When Septime arrived at Oregon Ballet Theatre to coach us, he entered the room with an infectious energy so robust it was simultaneously inspiring and intimidating. It was out with precious and in with a “rock ’em, sock ’em” attack, as he liked to say.

I quickly understood how this man was able to grow The Washington Ballet’s budget by %500 percent, attract well known talent, and develop a loyal audience during his tenure as Artistic Director there. Having the opportunity to meet with him from his Hong Kong home via zoom to talk about his production of Romeo and Juliet’s tour to the New York City Center only further developed my awe for this incredibly creative and energetic human. We dove into serendipity, creativity, research, and a love of storytelling in a way that has left me anxiously awaiting watching Hong Kong Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet at New York City Center January 13th and 14th!

Can you tell us a little bit about the creation of Romeo and Juliet and what the process was like?

I fell in love with Hong Kong when I moved here(from Washington DC) in 2017. For the previous 10 or 15 years, I almost exclusively had been making original full length ballets using great works of American literature. I knew I wanted to tackle a work that would reflect Hong Kong culture. The Hong Kong I fell in love with. I’m not the right choreographer to tackle Chinese literature. But I thought that something that would reflect the fusion nature of Hong Kong would be appropriate.

And of course, Prokofiev provides that amazing score. It’s almost choreographer proof. You can’t screw it up – it’s so good! I happen to have been a history major in undergrad during a period when I was essentially hiding from my parents how much I wanted to be a ballet dancer and telling them I would be a lawyer to deflect attention. I have always been interested in history and social context.

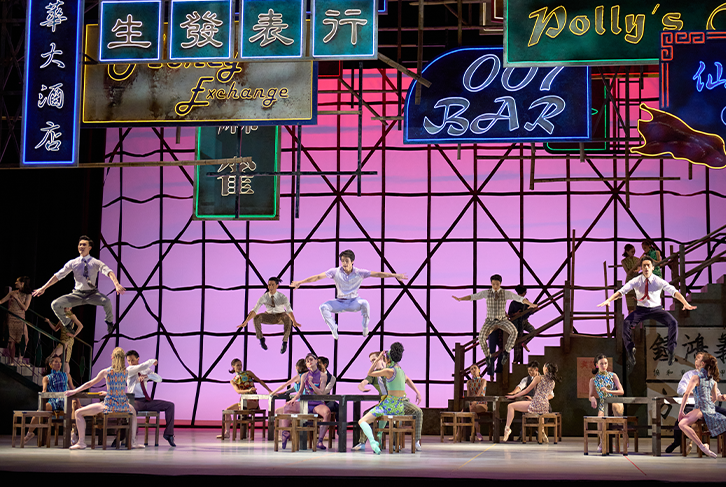

The early sixties in Hong Kong was a period of great social turbulence. There was a mass immigration from Shanghai to Hong Kong of people fleeing communism. It was a city that was becoming very wealthy and there were a lot of issues of class that seemed parallel to Romeo and Juliet.

I started the [choreographic] process in the early pandemic, so we had a long rehearsal period, but no performances scheduled yet because of the nature of the pandemic. Our dancers trained about six hours a week for quite some time in proper Hong Kong style Kung fu. So that’s another way that there’s a fusion – that the martial arts is woven into the ballet language. That’s a little bit of the genesis [of the piece].

This version is sort of a re-imagination of the classic Romeo and Juliet. What elements have been reimagined and what remains true to Shakespeare?

Well, when you’re making a big new work, there’s a lot of serendipity that’s involved in discovering how you’ll deal with different passages. The direct narrative essentials remain the same. There’s no real change in what happens, but characters and context have been adapted significantly. Here are maybe five or six small examples. Tai Po, the Tybalt role, is not only a triad up from the street, but he’s also a business partner to Juliet’s father and Juliet’s mother’s lover, adding another kind of family intrigue to the scenario.

The role of Friar Lawrence and essentially the Prince of Verona have been combined into Romeo’s Sifu- Romeo’s martial arts master. In Chinese culture, the Sifu is a master of any field. There’s thousands of years of apprenticeship tradition and mastering of a thing.

And often, Chinese medicine and martial arts are housed in the same person. That allowed this character of Romeo’s Sifu, both to be his kind of surrogate father figure, and also a kind of spiritual leader who might lead a symbolic commitment ceremony and also might know about medicines and give Juliet a potion.

During the early pandemic, there was a small opening [of stay at home restrictions] at some moment, during it, the city was relatively quiet. I was wandering through a neighborhood, thinking about the production, kind of absorbing the energy. I stumbled into a Mahjong parlor and I had played Mahjong as a kid in New York. I was fascinated.

It was so aggressive and chaotic and I thought, how brilliant. Actually, on my walk over there, I had been thinking about the fact that Prokofiev wrote a lot of music in Act two that doesn’t really tell the story; it’s yet another dance for the Harlot or for the street citizens. And it seemed redundant to act one and I thought, well, they’re going to stumble into a mahjong parlor. So I’ve created this really quite wild mahjong table that’s made a fun adaptation.

And that was one of those serendipitous kind of moments that you were talking about.

I was also scratching my head about how to deal with the Commedia dell’Arte, the first scene of Act Two. I was drinking a beer in Hong Kong’s Soho district one night, they had closed off the street and a film was being made. This is something you see all the time, films being made on the street.

So I thought, all right, we’ll have that be a film that comes by on the street. I hadn’t figured out what to do with that film and the next day I went for a meeting at the China Club here in Hong Kong in an iconic club that is in the 1930s Shanghai style.

There was a collection of comics from the 1960s of this character Lo Fu, Old Master Q. They would be the equivalent of Archie comics in the United States. It’s a funny old guy who’s really tall and skinny and his potato shaped friend, and they’re always after pretty girl Ms. Chan. Lo Fu is iconic in Hong Kong and so I knew Hong Kong people would know what it was. We changed the brand a bit because we didn’t quite have the rights for it.

One thing about Hong Kong is that street life is specific here. It’s very energetic. There’s food sold on the street. There’s kanji sellers and noodle sellers, dim sum sellers. So there’s a lot of little elements of street life that have been embedded in[to the production].

It’s so amazing hearing about your inspirations! It speaks to your creativity, in adapting the story, and it also speaks to Romeo and Juliet; that story that humans can relate to from all over the world.

You’ve already touched on your background studying history and falling in love with Hong Kong. How did you learn about all of these cultural references that you’ve been able to incorporate? Was it all through your own research or did you have people helping you?

I worked with a dramaturg, actually Yan Pat To, a local playwright and dramaturg based in Hong Kong with an international career – they helped me make some choices to ensure I didn’t make mistakes.

I mentioned I was a history major in undergrad and that I have a kind of eclectic background. My family traveled a lot when I was young. My six older brothers grew up in Cuba. I grew up in The Bahamas, South Texas, and Sudan. Spent a fair amount of time traveling in Europe as a kid. My worldview, I guess, is through an international lens and I am naturally drawn towards historical context; historical context of what’s happening around me or what the lineage is.

I did a lot of research and when I moved to Hong Kong, I just started to really soak in the city and really learn about it. Some of the elements come from the assistant of a wonderful dramaturg, some of it was just my own understanding of the city.

Some of it is just stuff where a light bulb went off – particularly the ballroom scene. I wanted it to feel like the early sixties. I wanted to show that the society was quite elevated so it would contrast from the street life. The designer has pushed the early sixties. Some of them have a Judy Jetson, atomic age, peplum to the Cheongsam that you would see at that time. Mac cosmetics designed the makeup and so there’s a lot of fun with early sixties liquid eyeliner and whatnot.

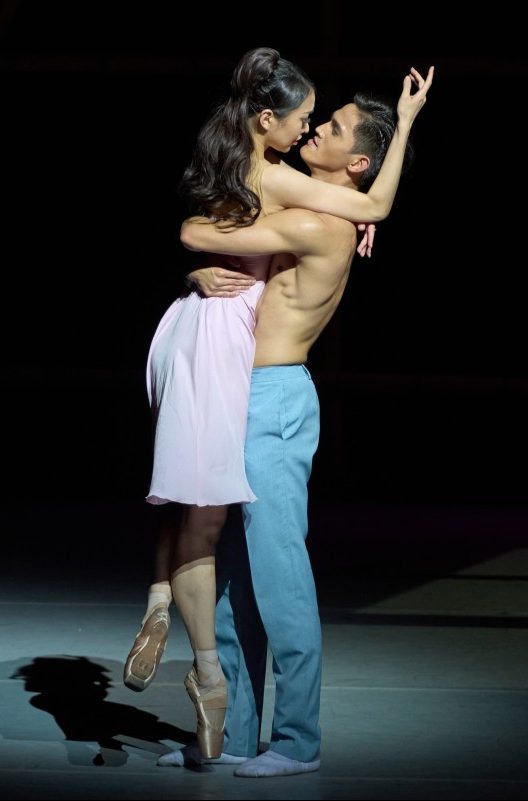

A lot of what we talk about now is kind of the context of design decisions. At the end of the day, the heart of the ballet though, is housed in that story and in the choreography and how the story manifests through this particular staging.

Images courtesy of Hong Kong Ballet.

You’re so fascinating and you share so much. I love it. Like you mentioned, you’re particularly well known and have a knack for telling stories of American literature and full-length ballets. How do you approach telling stories that we all know so well, and where do you think your innate ability for entertaining and storytelling came from?

I definitely came at storytelling organically. I came from the generation of artists who were influenced by Balanchine and Cunningham. And as a matter of fact, early in my career, I left ballet for a period and danced in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Serious choreographers weren’t making narratives. New work was generally abstract, shorter, and existed in a triple bill. I certainly came out of that.

Early in my career, I was an Artistic Director at Princeton Ballet. I was 30, and suddenly I wasn’t in charge of my choreographic career. I was a steward of a civic institution that needed some big ballets to grow the box office and grow the audience base. So I began to make work that did that. Initially, I used scores that existed, like Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella, The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, I adapted a Giselle, a Coppelia, all over the course of some years.

After this period of time, I felt ready to be my own author. I felt ready to tackle works where a score was not yet written. So about 10 years ago I created the first of these, a series of big ballets that were kind of from scratch. I looked to great works of literature and I created a Great Gatsby. I went back to the book, read it maybe twice cleanly, and then the third time began to make notes and imagine what scenes could be.

Essentially that became my process, and I came at it organically. I started as an abstract artist, and then eventually just naturally found my voice. Having said that, when I really realized I was a storyteller, I looked back to see where that came from and when I was a kid, I was naturally theatrical and I was a playwright.

When I was 10 I wrote my first play. It was called The Case of the Recurring Ennui. I had heard the word ennui, and I knew it meant something like boredom. My sister, who was eight, was my muse. She was wearing a white strapless, fishtail gown I’d made out of the canopy of her bed with safety pins and was lying on a chez I’d made out of suitcases and a red crushed-velvet blanket. As a Cuban-American, you don’t have to ask why I had a red crushed-velvet blanket.

I mean, stories just came naturally when I was a kid. And honestly, I’m just interested in the storytelling and I’m interested in technique and movement.

That’s so funny – you took me on this journey of your artistic maturation and process while also realizing that it all stems from the root of who you are as an entertainer and a storyteller.

I could do that for you because I am a storyteller.

You have worked all over the world. You’ve also, I found out, have lived all over the world. You are very multicultural and now you have this opportunity of bringing Hong Kong Ballet and Romeo and Juliet to New York City Center. What are you looking forward to, or what it means to you to have this tour?

It’s a terrific moment. It’s certainly a homecoming for me. I’m a New Yorker and a Washington DC person. Both cities are home to me and City Center is the epicenter of so much important dance over the last 75 years or more.

I’m also excited because I came to Hong Kong Ballet in 2017 and Hong Kong Ballet is, and was already, a beautiful ballet with a great bone structure and a really elegant repertoire.

What I hope I have brought, is a fresh energy to it. I’m anxious to share this re-energized company with New York and with American audiences. It’s also a really great celebration for Hong Kong.

During the pandemic we’ve been so isolated. Everyone’s been isolated. I’m happy for Hong Kong Ballet to be the first major kind of cultural ambassadorship from Hong Kong to the world to remind everyone of the energy and special nature of Hong Kong. Hong Kong’s also a city that has a special glamor to it and I think you’ll see a little bit of that with the company as well. The company definitely reflects the energy of the city.

Well, I am so happy to chat, chat with you and reconnect and I am looking forward to seeing you in New York.

Me too! Thank you so much for taking the time to chat.