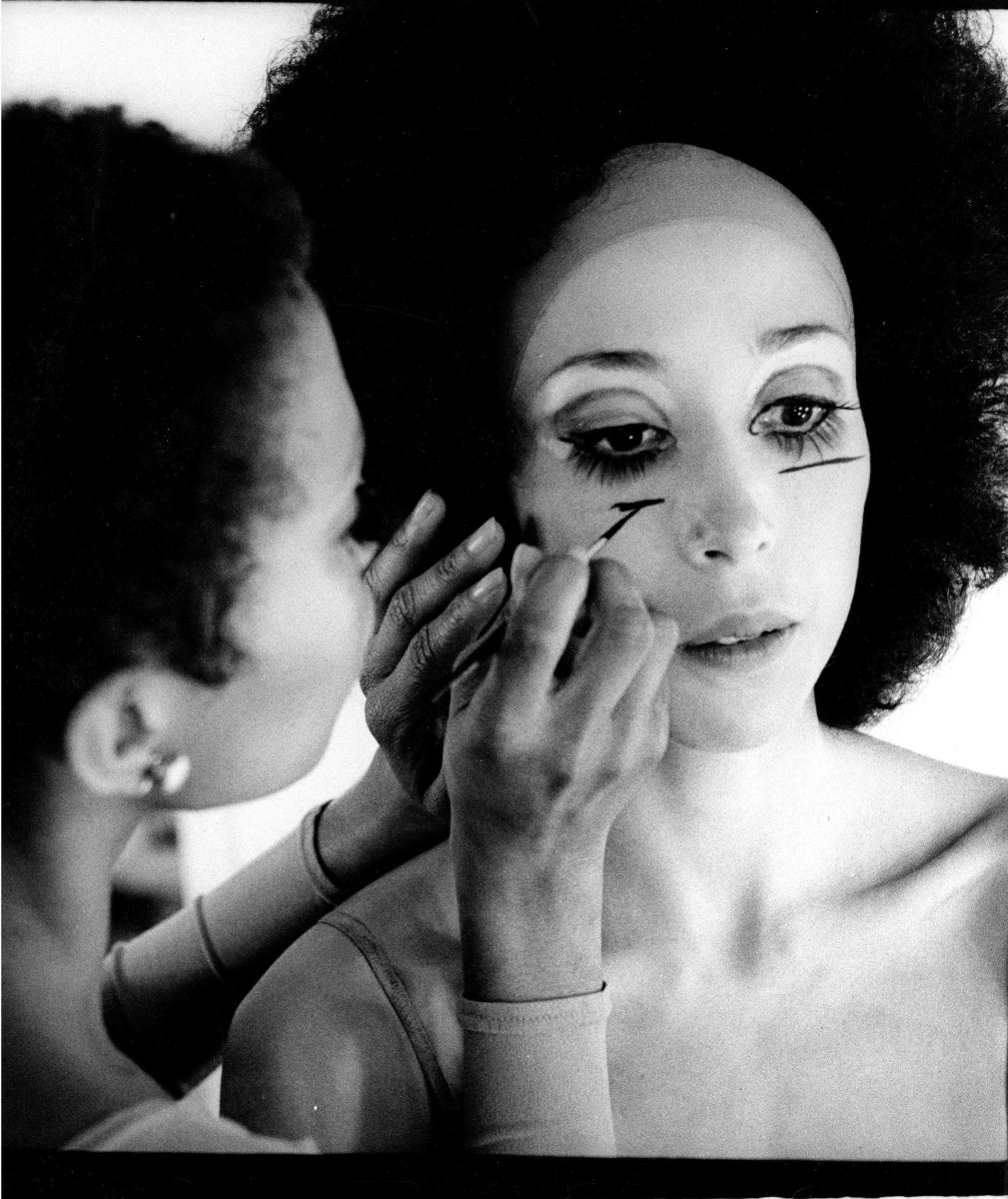

Virginia Johnson by Sasha Nialla.

By Djassi DaCosta Johnson

American ballet pioneer, cultural icon, and change maker.

It is 2023, and theater and live entertainment are back and seemingly stronger and more inclusive than ever. One of the benefits of the pandemic and the “Great Uprising” of 2020 were the subsequent implementations of the equity, diversity and inclusion culture throughout various sectors stifled for decades by exclusionary, elitist cultures. Another benefit that arose from these past transformative years, was a heightened visibility of the art world and ‘small sector’ issues thrust into the larger media platform. The world of classical ballet experienced public criticism and exposure of both the sexism and racism that have been woven into the culture of ballet from its birth in the French royal courts of Louis XIV in the 15th century. Now, finally, in 2023, following an increase in the conversations and initiatives that have been brushed under the table for decades, there is real, and actual visible change happening—displaying diversity and opening doors for American ballet to evolve into the inclusionary art form that it was actually intended to be.

To present a comprehensive retrospective on the expansive career and impact of a figure like prolific ballerina, educator, writer, editor and Artistic Director Virginia Johnson, it is necessary to expand the umbrella under which we view her career. Johnson has established herself as a formidable artist in her own right, but through the combination of history, geographical fortune and divine encounters, her personal artistic history is intrinsically woven within the actual and intended roots of American classical ballet. Roots that were born from the vision of a Russian ballet dancer and choreographer named George Balanchine.

Virginia Johnson and fellow female dancer applying makeup before a performance. Photo by Marbeth.

The story could be said to have actually started in 1933 when the impresario Lincoln Kirstein wrote a letter introducing his new friend, Balanchine, and their joint aspirations to start a new ballet company to a director in Hartford. Kirstein called for a core of “16 dancers, half women, half men, half white and half negro.” What eventually resulted was the creation of the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet. However, as we know, their joint plan for a diverse student body was never realized, as they were consistently blocked by administrative constraints. It took 36 years for anything close to what they envisioned to be birthed, and Virginia Johnson arrived in New York City at the perfect moment to become a part of that defining moment in history.

On and off the stage, Johnson has had a decisively pioneering career. As an integral part of the legacy of Dance Theatre of Harlem, her career as an influential ballerina coupled with her intellectual influence on the world of ballet cannot be understated. Hailing from Washington D.C. and studying from the age of three with the pioneering Therrell Smith, Johnson received a scholarship to The Washington School of Ballet where she trained under Mary Day and honed her stellar technical foundation while being told, famously, that although she was a beautiful dancer, she would “never work as a ballerina” because she was Black. Upon graduation, Johnson decided to leave for New York City to study dance at NYU where she met New York City Ballet dancer Arthur Mitchell in a class he taught. She left to help him start Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969.

The Black and brown ballet bodies, faces, and names that we now know and see emerging more frequently across national and international dance companies and gracing the covers of magazines in an unprecedented way sprang from this birth. A handful of select dancers have led the way over decades and now, these current advancements in diversifying the field are the matured and blossomed fruits of the seeds planted with the founding of DTH by Arthur Mitchell. After fourteen years as the first Black principal dancer in the New York City Ballet, and despite being Balanchine’s muse in many ways, Mitchell’s legacy is fortified through becoming the vehicle for which the original vision of American ballet was finally realized. Many may, or may not, know the inception story of Dance Theatre of Harlem. It was the brainchild of Mitchell’s. While on his way to teach ballet in Brazil, upon hearing of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the radio, he decided to return home to start a school for ‘his people’, right in Harlem, enlisting the mentorship of Balanchine and the partnership of Karel Shook, teacher and co-founder of Dance Theatre of Harlem. Mitchell first started the school in 1968 and then the touring company in 1969, of which Johnson was a founding member. In an interview from 2017, Johnson recalls:

“In that first company we were an extremely diverse group of people. There were Asians, there were Mexicans, there were Black people . . . I think the first white dancer didn’t come until 1970 but as I say— and it’s so important that right from the beginning the idea was that “diversity was the richness” and that was very oppositional to the way that ballet was moving in the 1950s and 60s and 70s in this country where “sameness” became important as what was signified in ballet.”

Virginia Johnson and partner dancing the mad scene in Giselle, Courtesy of Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Through her work as a ballerina, Johnson has literally ‘set the barre’ and helped usher many dancers to prolific careers. However, it has been her work outside of the studio and the stage, that has helped elevate the conversations about ballet, inclusion and access to the art form. She was the founding editor of Pointe Magazine and is one of the leading voices in the advancement of ballet as a co-creator of The Equity Project: Increasing the Presence of Black People in Ballet. Through her teaching, advocacy and work with the school and company, Johnson has made clear that she embodies the mission of DTH and Mitchell’s dream. When speaking of this, Johnson emphasizes:

“The idea of Dance Theatre of Harlem wasn’t to create an exclusively Black ballet company,” she says. “It was to make people aware of the fact that this beautiful art form actually belongs to and can be done by anyone. Arthur Mitchell created this space for a lot of people who had been told ‘you can’t do this’; to give them a chance to do what they dreamed of.”

Virginia Johnson and Company, photo by Andrea Mohin © New York Times.

In the past five years, notably, there has been an increase in calling out the rampant racism within the ballet culture and community. Ballet institutions are finally being forced to address the systemic racism embedded in the art form, placing dancers of color at the forefront as principal dancers, choreographers and Artistic Directors in numbers never seen before. It is a notable reality that less than a decade ago, Black and brown ballet dancers not only had a hard time finding employment in their field, but it has been customary to only see a handful of names and token dancers of color sprinkled throughout the vast landscape of classical and contemporary ballet.

Watching DTH today, the impact is clear. Whether in the diverse international casting, the classical and innovative repertory the company performs, the many ballet stars and pioneers that began their careers at DTH, to the revolutionary impact of its re-emergence in the global ballet scene, we are seeing today what Johnson exalts as “the prevailing sense of self-affirmation behind DTH” that was integral to Mr. Mitchell’s vision.

Johnson showed her commitment to that vision when she stepped in, as Mitchell’s hand-picked successor, to become the next Artistic Director and steward of the re-emergence of DTH’s professional touring company after its eight-year hiatus due to budgetary issues from 2004–2012. She has been responsible for the company’s resurgence as one of the premiere American ballet companies and, the only, truly, ethnically diverse ballet institution internationally. Through this lens, it can be said that Mitchell, considered to be Balanchine’s muse and one of many who offered Balanchine a lens into Black American dance and culture, realized the vision that Balanchine and Kirstein only dreamed of in those early years. Johnson’s work has furthered Mitchell’s vision by expanding outside of just one institution, influencing the ballet schools and stages of the world while extending the opportunities for access to ballet for all with a passion for the art form.

Virginia Johnson and Company at a rehearsal.

After a historical decade at the helm of the company, Johnson will become Artistic Director Emerita in July 2023, leaving a legacy that is living, breathing and evolving as we close this 2023 season in celebration of her.

Virginia Johnson’s legacy is not just in being a cultural icon, a living artistic example, and educator to so many who strove to pursue the career of ballet, but in taking advantage of her place in history, she was poised to help keep the art form elevated while the culture of ballet evolved past the origin of its prejudices to rise to the vision of what the art form could truly be. When speaking of the void that was felt when the company was on hiatus, Johnson reflected: “There was a generation of little girls who didn’t see brown ballerinas . . . they didn’t have that seed planted of ‘I could be up there too, I want to be a part of that!’ so we really need to rebuild that sense of inspiring another generation of dancers to come forward.”

As Johnson passes the torch, she leaves DTH having not only inspired new generations of dancers to emerge but having helped usher forth a new face of classical ballet that will continue to evolve and inspire excellence on, and off the stage. As Johnson has said of Mitchell’s mission, it “made people aware of the fact that this beautiful art form actually belongs to . . . and can be done by anyone . . . and of the fact that they can define their own identity. That you don’t have to be defined by somebody else’s perception of you.”

This article is published her courtesy of Dance Theatre of Harlem. It first appeared in the Dance Theatre of Harlem 2023 playbill by En Face Magazine. Check out the full playbill HERE.