When you think of ballet, two iconic symbols likely come to mind—the pointe shoe and the tutu skirt.

Layers of tulle encircling a pirouetting ballerina may seem timeless to us, but both ballet technique and costume design have undergone dramatic transformations over the centuries.

Each transformation pushed the envelope further, both in athletic prowess and grace as well as how much of the ballet dancer’s body could be seen by the audience. While they may have caused some pearls to be clutched in their time, each scandalous slashing of the skirt freed ballet to develop the breathtakingly classic and elegant style we now know it for today.

Join us for a quick tour of the tutu timeline as we watch the hemlines.

COURT DRESS

Let’s go back in time to the 1600s and the French royal courts of Louis XIV. At the time ballet was only just coming into being —the pointe shoe didn’t even exist and men took center stage while women were relegated to supporting roles. One simple reason women were not central in the choreography was due to how cumbersome their courtly clothing was. In traditional Court Dress, many heavy layers of fabric draped to the floor, meaning that very little, if any, footwork could be seen while dancing.

ROMANTIC TUTU

By the 1800s women had begun to step into the spotlight and ballet was developing a defined technique. Marie Taglioni became one of the first women to dance on the very tips of her toes, bringing pointe work into ballet vocabulary forever. Her delicate footwork and softly floating jumps were further highlighted by her diaphanous costumes that featured hemlines that ended partway up her calf. This style, known as the Romantic Tutu, launched an era of pale, gauzy, floating tutus that made the ballet dancer appear as if she was stepping out of a hazy dream.

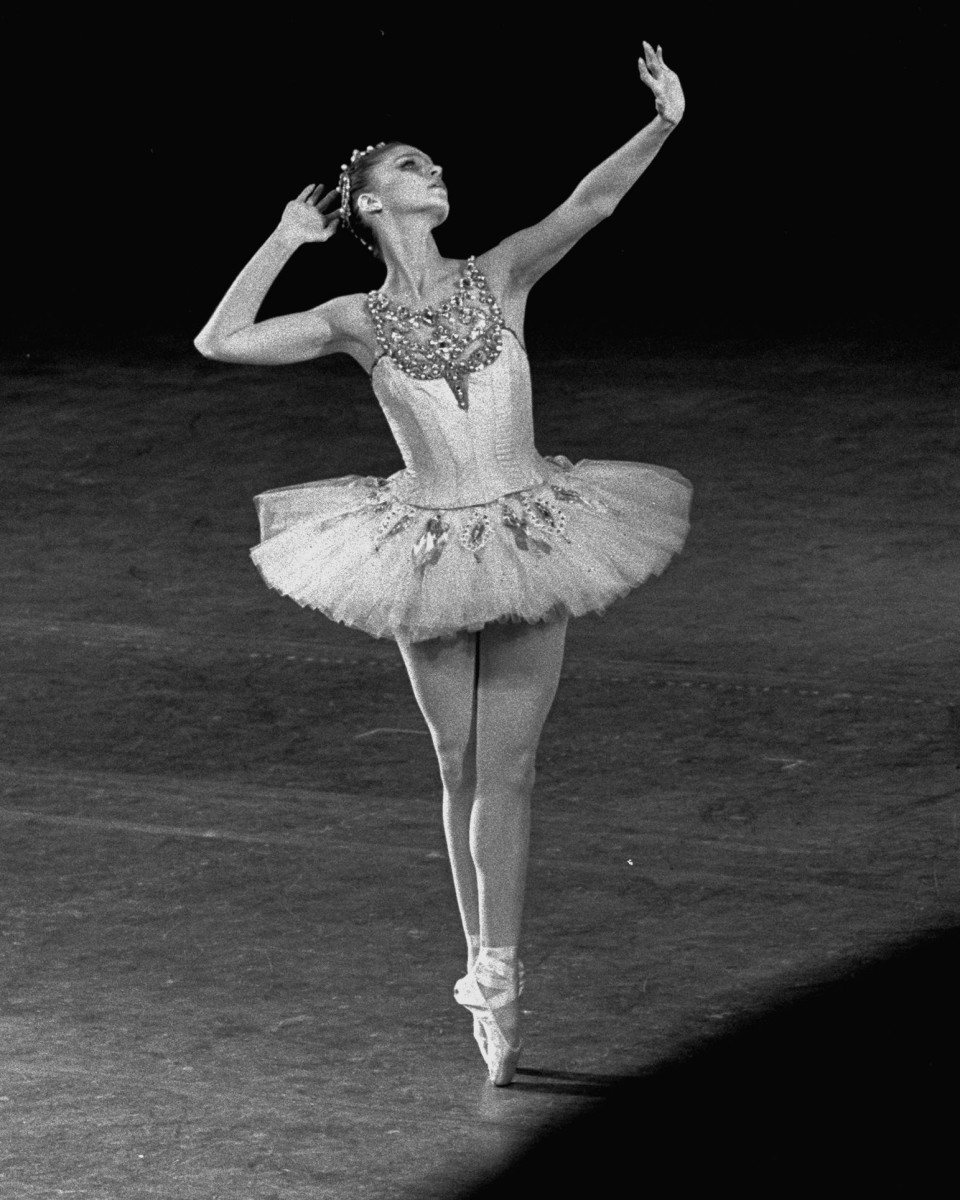

CLASSIC TUTU

Once dancing en pointe entered the ballet conversation, the emphasis on training and technique began to accelerate. This greater focus on skill and precision made it paramount that the audience see the newly heightened athleticism and beauty in action. Thankfully the development of industrialized fabric production made tulle more accessible to costume departments, and with this new material, the skirts rose up to the knees and even slightly above them. The resulting Classical Tutu was defined by a blend of delicate visuals and practical design which empowered dancers to focus on their craft.

PANCAKE AND POWDER PUFF TUTUS

As ballet stepped into a new era in the 1900s, George Balanchine founded New York City Ballet and defined the look of ballet for a generation. Clean, sleek, and minimal became virtues to strive for both in movement and in costume. Tutus reached their shortest lengths at just below or right at the waist, and instead of draping downwards, jutted straight out thanks to the inclusion of wires and stiffened materials. The Pancake Tutu was flat and crisply structured to complement bold choreography, while the Powder Puff Tutu was constructed of short, frothy layers of tulle which highlighted light and whimsical movements.

Which of these pivotal tutu styles is your favorite and which ballet have you seen it featured in? Let us know in the comments!