Feature image of Misty Copeland as Juliet in Kenneth Macmillan’s Romeo and Juliet. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy American Ballet Theatre.

On an unusually cold evening in late March, I nestled on my couch with my feet up after a long day. I caressed my belly to soothe my growing son, who was in a restless mood, kicking up a storm. With his “grands battements,” he seemed eager to let me know he wanted to “get out” and see the world, and I certainly couldn’t wait to meet him.

I lay back, eating sunflower seeds—my favorite snack as a child had become somewhat of a comfort food now that I was an adult. As I cracked open the salty shells, I wondered if my son would enjoy them like I had with my dad. Already, I was assessing the world around me, from the smallest, most ordinary items, like my favorite snack, to the largest challenges, like the state of the justice system and the destruction of the environment, in terms of how they would affect him. Like I imagine most mothers who are expecting do, I fantasized about introducing my child to my many loves that make life beautiful: music, from Mariah Carey to Beethoven, Japanese gardens, and Marius Petipa ballets. But I also worried about the realities of bringing a Black boy into the world—exposing him to the war, racism, and inequality that are part of our current reality. I am so grateful to have an incredible partner in parenthood, my husband, Olu.

Even though our nation had made so much progress, and the reckoning in the wake of the murder of George Floyd had brought so many honest conversations to the forefront, like countless Black mothers before me, I nursed high hopes and huge fears about what the future held for my boy. Who would my son be? What would he want to become? Would he find himself one of only a handful, a “rare” and highly scrutinized few in the field he was most passionate about? Would doors be open to him, or would he have to break them down with the help of so many others who had tried before him? I couldn’t help but think of my own journey to being “the first” Black female principal dancer at American Ballet Theatre. I wanted his path to be smoother, but in the pit of my stomach, I grappled with a deep anxiety that it wouldn’t be.

That night, I didn’t feel like reading or binge‑watching a favorite series. The Senate hearings for the confirmation of Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson were in full swing. I wanted to witness history in the making, so I turned on C‑SPAN to see what I’d missed that day.

Judge Brown Jackson sat calmly at the table, her hands neatly folded before her, maintaining her composure as questioner after questioner sought to paint her as “soft on child pornographers” in her sentencing practices, interrupting her as she attempted to answer, and distorting her record beyond recognition. She never raised her voice; she never lost her temper in a situation in which any normal human being would have been justified in exploding. I watched her in one moment literally swallow her outrage and take a breath before responding evenly and respectfully with well‑reasoned facts. I believed I knew what kept her centered. As I watched her sit there stoically, taking everything that was thrown at her, I imagined she was thinking: “I’m the first. I’m in the room. Many fought for me to be here. No one said it would be easy. There are those who are determined to see me live up to every stereotype of the emotionally undisciplined angry Black woman, and I won’t. This is bigger than just me.”

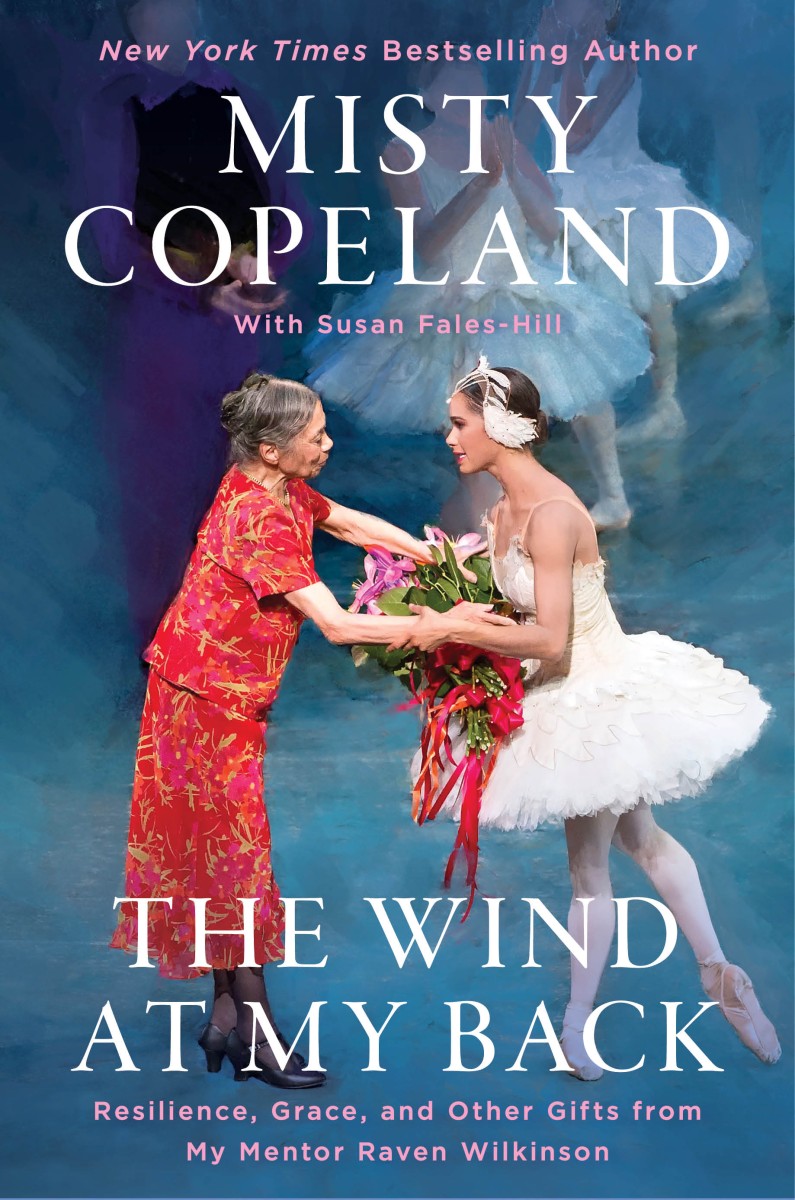

Excerpted from the book THE WIND AT MY BACK: Resilience, Grace, and Other Gifts from My Mentor, Raven Wilkinson by Misty Copeland with Susan Fales-Hill. Copyright © 2022 by Misty Copeland. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.